The first time I ever witnessed the widespread wearing of face masks outside of a medical facility coincided with my first trip to Asia. Last year I went to Japan to meet with members of the Tokyo ruck club and facilitate several GORUCK events. I invited my mom to accompany me to the place where she had lived when her father was stationed at Green Park Air Force Housing complex in Tachikawa, a city located in the western portion of the Tokyo metropolitan area. This was to be the return trip of a lifetime.

A walk down memory lane

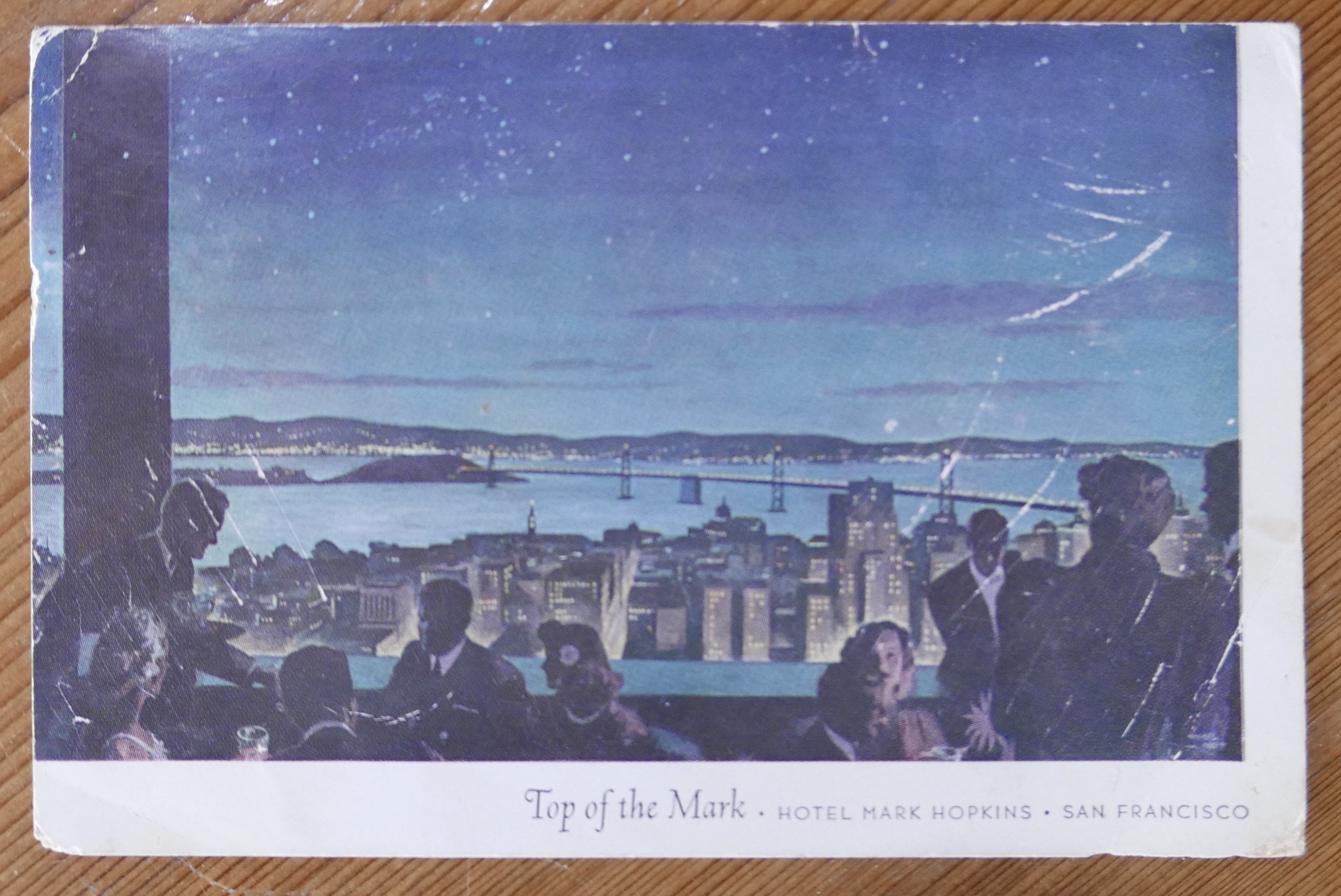

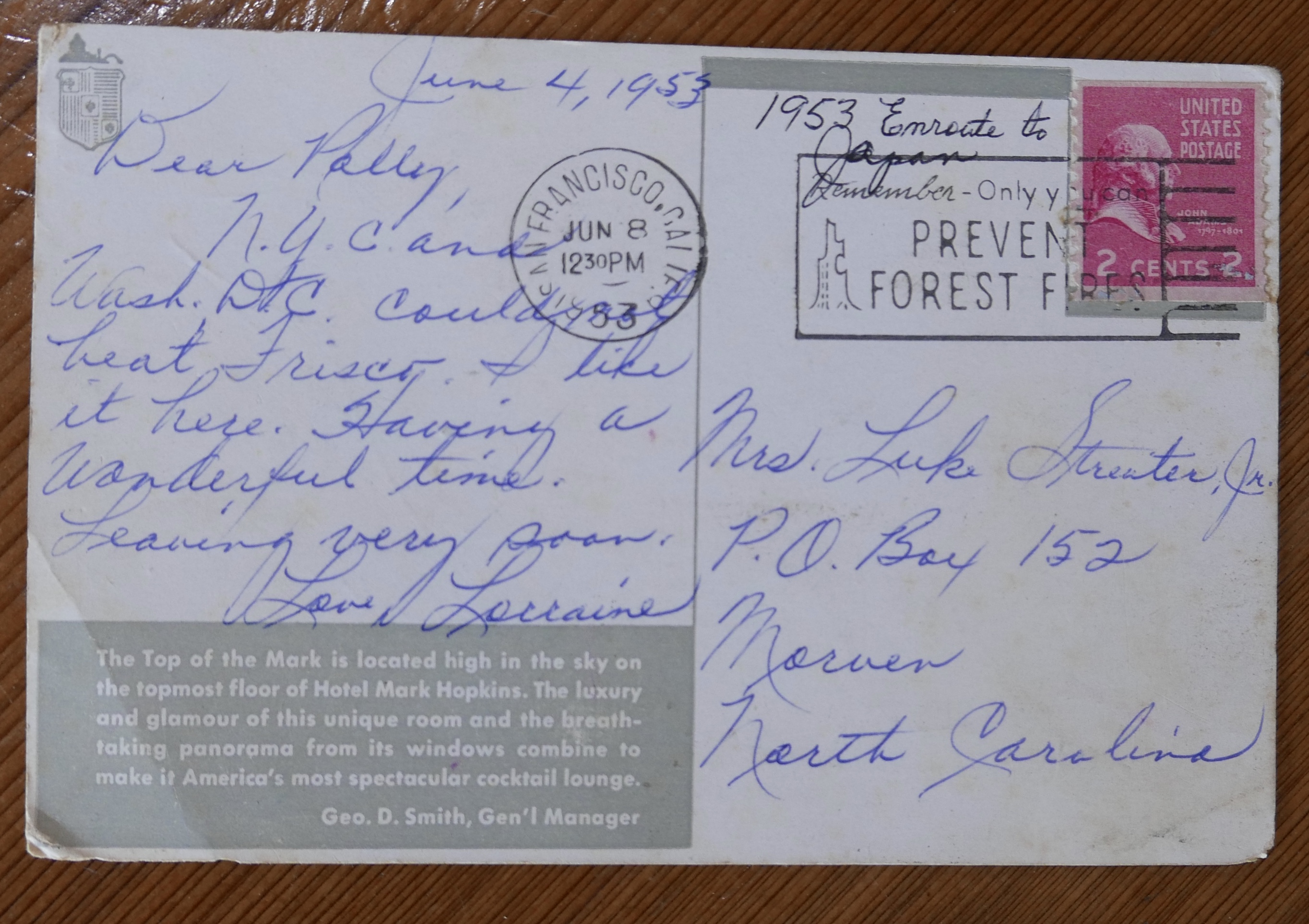

The American Occupation of Japan had officially come to an end in 1952 within a month of my mother’s birth. After earning a Purple Heart in WWII on the European Front, her father was shipped off to Yokohama on January 31, 1953. The anchor dropped in Japanese waters on February 15, 1953 – the same day as the birth of his third child, my mom’s younger brother. My grandfather soon found out that he could bring his family with him so he returned to Wadesboro, North Carolina (where my grandmother was originally from), packed up the family, and drove everyone to San Francisco to board a ship. They arrived to Japan on June 18, 1953 to start a new life.

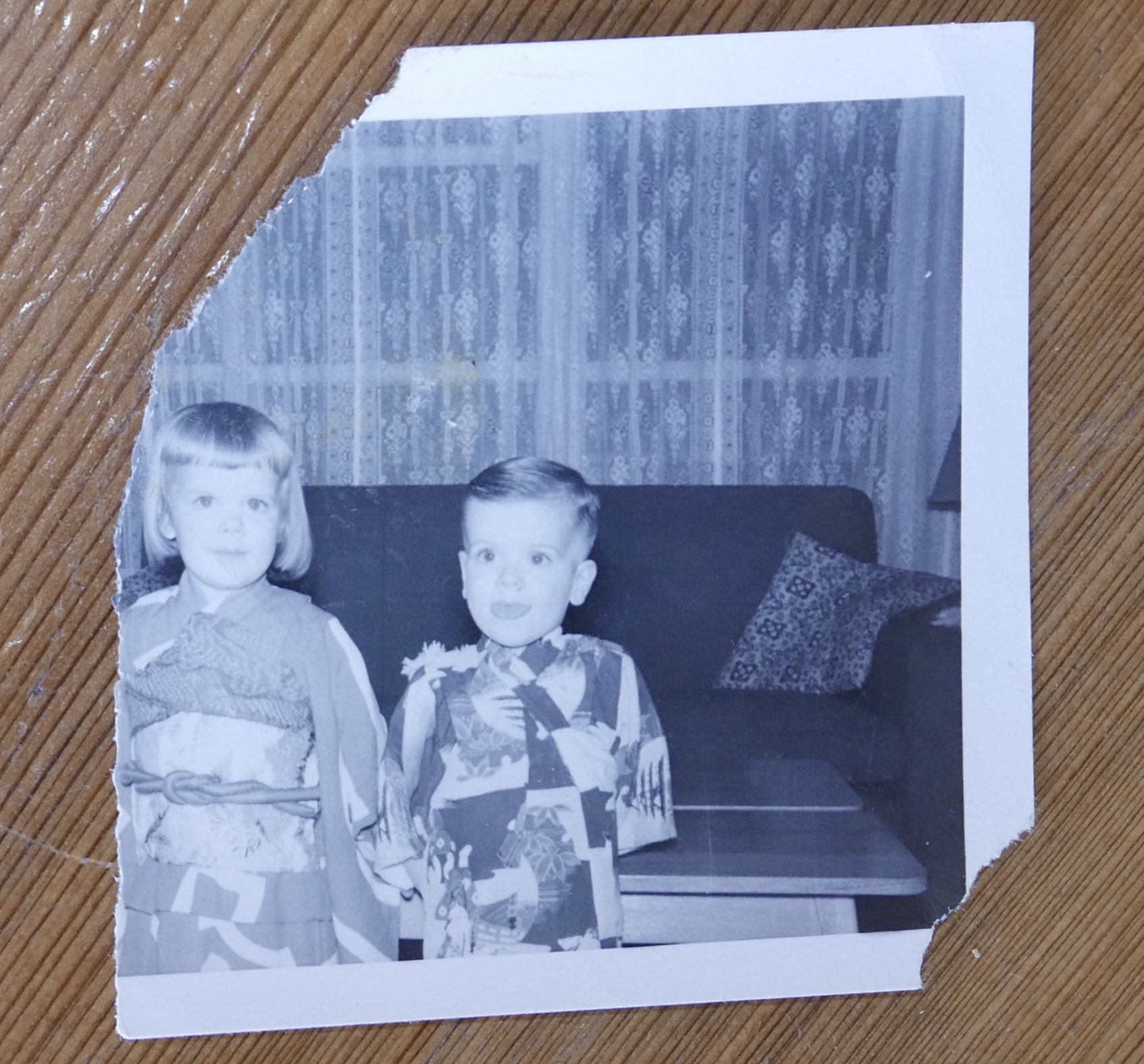

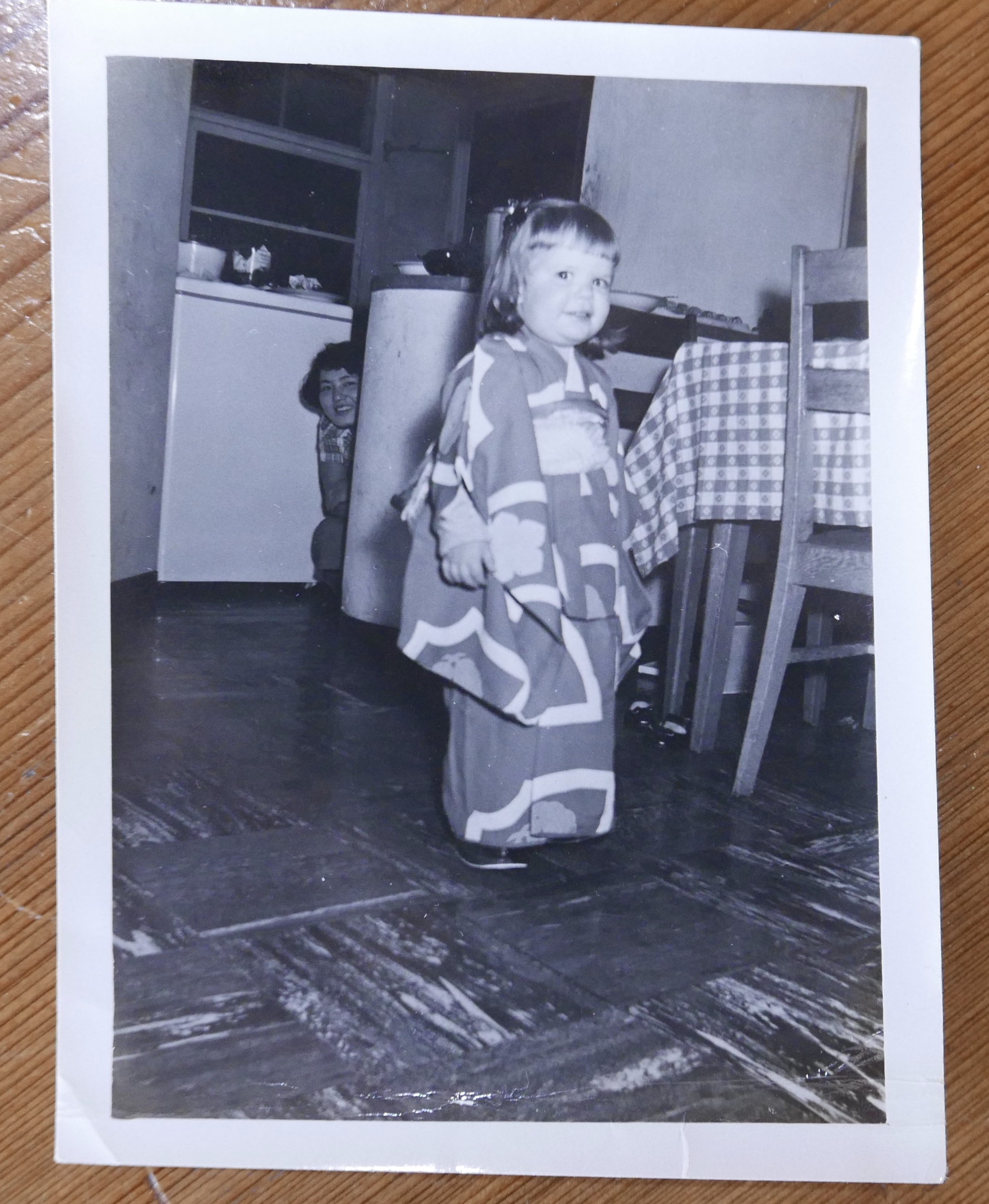

I’ve heard stories that, at first, my grandmother hated the thought of uprooting her young family and moving across the world to Japan. She did not enjoy living in the “rice patty” houses for over a year and described the country as rural, somewhat primitive. In the 50’s, Japan was not yet the world’s third largest economy and life looked a lot different in general. As time passed, my mother’s family moved to base housing with a dedicated staff, Gingko-san the nanny and Robert-san referred to as the house boy. Allegedly, my grandmother began enjoying life in Japan so much that she did not want to leave when the tour came to an end. My mother has vague, happy memories of her time in Japan since she was only 3.5 years old when they repatriated to the United States. However, she does vividly recall one incident when she was playing with a purse on her balcony. She and her older sister were given permission to play with the little girl who lived across the hall. Out of pure excitement, the little girl accidentally ran through the sliding glass door in her apartment, shattering it and getting blood everywhere. My mom remembers Robert-san carrying the little girl to get help.

Adaptation is an observable fact of life

Fast forward about 65 years, my mother and I are about to touch down at Haneda International Airport. Before we could disembark, masked agents came down the aisles with infrared thermometers to scan passengers for any feverish conditions. We might as well have landed on Mars, I had never seen anything like that before in my life. It turned out that in spite of warnings of culture shock and a soft landing from our GORUCK community on the ground, I was unprepared for certain Japanese customs, namely those dealing with personal hygiene. Where can I wear my shoes? Is it ok to hug or only bow? Is rubbing your chopsticks together rude? I was in a constant state of mild worry that I was offending someone and unaware that I was doing so.

Tokyo is one of the most populated cities in the world with about 38 million people in the greater metro area. And on top of that, it’s super dense with just over 6,000 people per square kilometer. That’s a lot of people living in close proximity to one another. Over their modern history, the Japanese have dealt with the effects of novel viruses such as the Spanish flu, Asian flu, Hong Kong flu, SARS, H1N1, and now Coronavirus. In other words, they know what to do in case of a sudden outbreak. I was accustomed to big cities and yet unprepared to see so many people wearing masks out in public. It gave me a strange feeling of apprehension for not wearing one myself. Was I being unsanitary or unsafe?

In the days that followed, the sci-fi morphed into a series of Lost in Translation moments, filled with awkward but distantly friendly exchanges with locals wearing masks and a lot of Google Translate to communicate. I quickly learned that showing my phone to the taxi driver was a lot better for everyone than me butchering the Japanese phrases. It was helpful to see Cadre Doug, an American Special Forces veteran, wearing a face mask to lead the GORUCK events. I asked him why he had one on and he told me that he had been sick and didn’t want to spread germs. Ok, so just a considerate precaution. That made sense.

Toward the end of our trip, we took a train to check out Tachikawa and see Mt. Fuji. Because the cherry blossoms were starting to bloom, it was hanami aka peak travel season for flower viewing and hotel options were very limited. As a result, we ended up staying in a much fancier onsen than necessary. I rationalized the spend by asking myself when would my mom and I ever have the opportunity to come back to Japan. In retrospect, I’m glad we lived up that moment. Chances are slim that the two of us will be back in Asia anytime soon.

While at this fine establishment, I thought it’d be nice to have the items I wore for the GORUCK event washed and have Marie Kondo-like folded clothes for the trip home, so I called the front desk to inquire about laundry service. There was a lot of confusion and scrambling on the other end of the phone. A few minutes later, there was a knock on our room door. I was politely told that the staff could not wash the clothes of guests because it was unsanitary. If you are sensing a theme here, you are right. I was feeling pretty dirty for someone who wanted to have clean clothes.

Suffice it to say that Japan challenged my notion of personal hygiene and social responsibility. Until that trip, I had always considered myself to be a fastidious person. I’m the type who opens public doors with my foot or shoulder to avoid touching the handle with my hands. I also build a nest or hover over public toilet seats, sometimes without even taking my ruck off (it’s a good burn, try it sometime). And this concept of turning off the faucet with the paper towel? Been doing it for years.

Following our trip to Japan, I thought a lot about my grandmother – how she faced the unknown, adapted, and grew to love a culture so foreign to her. I’ve since made some adaptations of my own while keeping Japanese culture in mind; new habits that have proven to be meaningful in a pandemic.

How to make small adaptions to your life

-

- Wear a face mask. Last year prior to the pandemic and because of my time in Japan, I added a face mask to my essential packing list for travel. I started wearing it in crowded places like airplanes or airport shuttles, even once around my house when I was fighting a cold. Nowadays, I wear a face mask to the grocery store and any other place where I could come into close contact with individuals outside of my quarantine.

- Don’t allow shoes inside or on carpet. This is a great custom from the Japanese though it can be difficult to enforce in American society. I have several spots for shoes near the front door, both inside and outside of the house. Having footwear confined to certain areas keeps the house cleaner and more organized.

- Consider using an alternate greeting to the handshake. Bowing is cool but it takes some getting used to for us Americans brought up on the importance of a strong handshake. Lately I’ve been using a simple wave and a smile.

- Maximize time outdoors. When you have the choice, choose to be outside. Fresh air has a lot of benefits and fewer germs floating around is just one of them. Tokyo Hikyaku Ruckers have adapted well to their online training sessions during there now extended lockdown but I know they can’t wait to get back on their training field next to Tokyo Tower.

Our Face Masks will be back in stock mid-May. You can sign up for email notifications here.

Featured Gear:

Your small adaptation to not allowing footwear into your home is a smart thing to do as it helps to keep your living area clean (or making it easier to clean when it is time). You are correct when you say it might be more difficult to enforce in the U.S. but ask people where they were before they came to your house and what they stepped in before their arrival. Ever been to a public latrine, especially a male latrine? Ever see what you are standing in when you are in front of a urinal…and you bring that into a house? Places such as Hawaii, which has a high concentration of citizens who are of Asian descent have no problems sitting on floors and more often than not, do so in preference to sitting on a chair/couch especially in the living room; yet another thing to consider when you have babies who are crawling on the floor and are concerned for their health. If you look up the word “genkan” online, you can see examples of areas where shoes are removed and kept (which I’m sure you saw while in Japan). If the genkan is recessed to around calf level, it might be easier to put your shoes back on but for those that are only several inches high, you may want to have a bench of sorts (or chair) where people can sit and put their shoes back on. A separate carpeted area near the door can serve as a genkan and also makes it easy to clean by vacuuming/washing when needed. Great read and thanks!

I’ve never quite understood the level of opposition I get when I ask guests to remove their shoes before entering our home. We have slippers if they want, but I’ve had guests refuse and choose to leave. I grew up in the US and was rarely a problem in NY, but in Maryland and Virginia I seem to run into more nasty looks when I ask. The only person who left was a guest of a friend, so didn’t know them personally.

I’d like to see Goruck set an example for safety with masks and distance in some marketing and required in events or any group rucking. Our nation is in bad shape over the pandemic and prevention is the responsibility of all, not an individual choice.