“If Al-Qaeda is the guy outside your house with a shotgun, Hezbollah is the guy already holding a gun to your head,” a senior officer presented this chilling perspective while I sat in a briefing on terrorist threats during my time in the Agency. In other words, are you focusing your intel collection efforts on the most immediate threat to national security and what sort of risks are you willing to take to obtain it?

That movie scene-worthy line hit me a little bit differently from where I was sitting that day, namely as someone who had been working in the field for several years. I hadn’t seen everything but I had seen enough to know that the greatest risks most likely did not look like a terrorist kidnapping while I conducted a surveillance detection route or slept in my bed. When people ask me about the nature of that job, I tell them to read (not watch) the Red Sparrow trilogy written by a former intel officer, only take out all the sex and violence to get a pretty accurate picture.

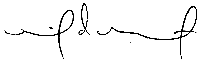

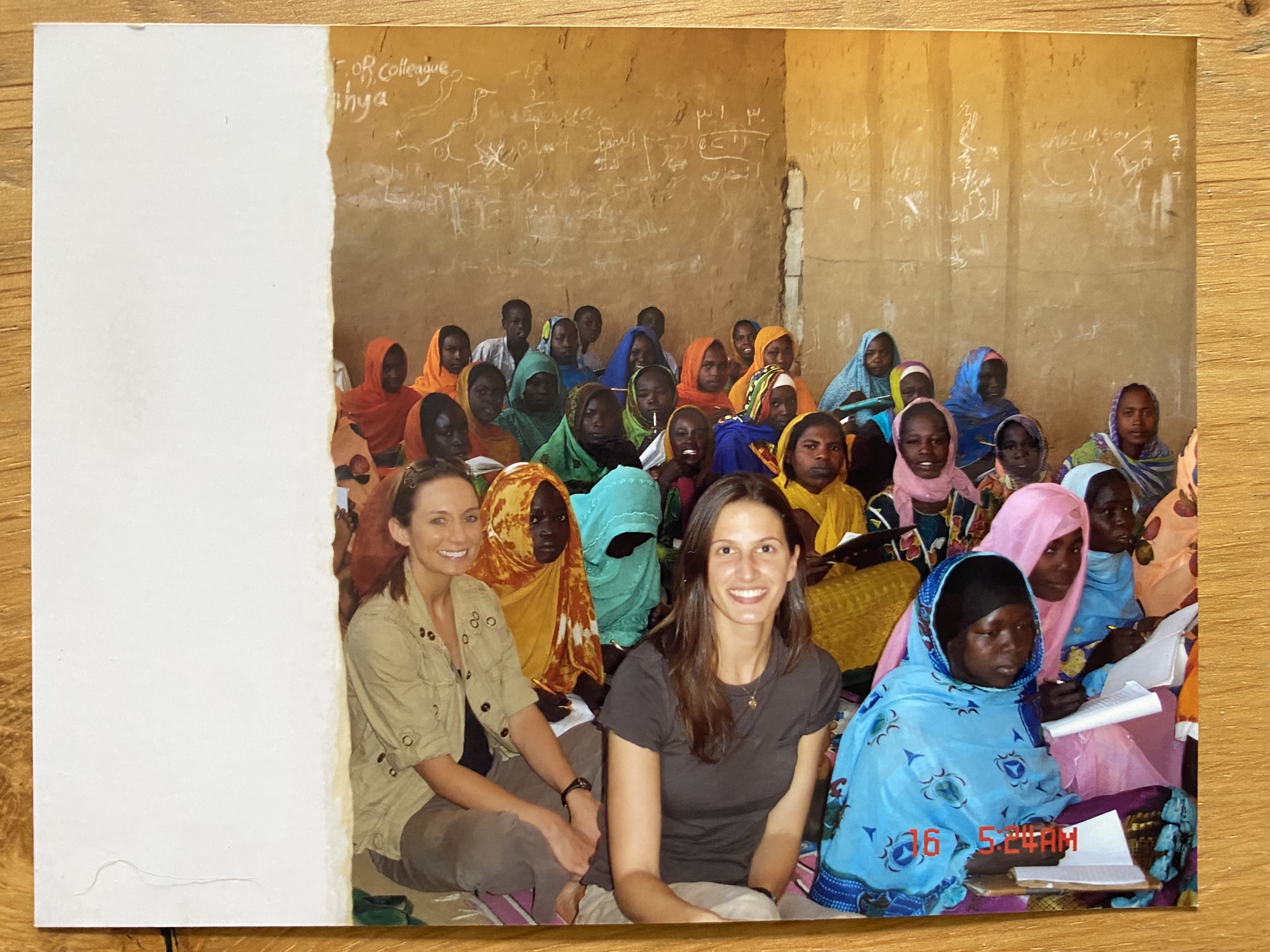

As a lone case officer working out of small stations in West Africa, I used to tell myself that the cavalry wasn’t coming. Ultimately, I was responsible for my own safety and for conducting my own assessment of the risks I faced. These were not the risks usually found in spy novels and movies. They were more mundane, like the fact that my “golden hour”, or the period of time immediately following a traumatic injury during which prompt medical attention can prevent death, was significantly reduced the farther I ventured from a working hospital. As a telling illustration, a few months after I arrived to post, a Foreign Service National driver lost his only son because he bled out following an altercation that occurred outside of the city.

I would spend late nights meeting with the type of person who wants to get paid for stealing secrets. Moreover, and what I found to be the most precarious, was having to terminate a source by informing them that their services were no longer needed, thus delivering what was often a crushing (financial) blow. To mitigate some of the biggest risks I faced, I took training courses on emergency medicine and bought a book called Where There Are No Doctors that I still refer to today while living stateside. I brought along a protective chocolate labrador retriever as a makeshift bodyguard to my asset meetings. And when running a termination meeting, I made sure to allow the source to walk away with their dignity (and a wad of cash).

In many ways, my appetite for the type of risks I faced while in my 20s with no children while living and working abroad for the USG has changed. I’m no longer breezy about having a rifle pointed at my head at a checkpoint. There are risks I took then that I would not choose to take now as a mother of three. Today, the likelihood of driving through armed checkpoints is low, however my risk of dying of heart disease (the leading cause of death for both men and women) is elevated given my age and family history. So I do what I can: stay active, eat healthy most of the time, and go see a cardiologist for a full check up every five years.

The truth is that you can not live this kind of life, or any life for that matter, without taking on some risk. No successful case officers sit in their office reading reports all day long; likewise, no successful parent keeps their child in a protective bubble forever. You have to put yourself (and, over time, your children) out there and assume some risk, at least until the day comes when you no longer can.

http://biotpharm.com/# over the counter antibiotics

Over the counter antibiotics for infection: Biot Pharm – buy antibiotics for uti

commander Kamagra en ligne: kamagra en ligne – kamagra pas cher